THE DOGRUN

a place to share ideas

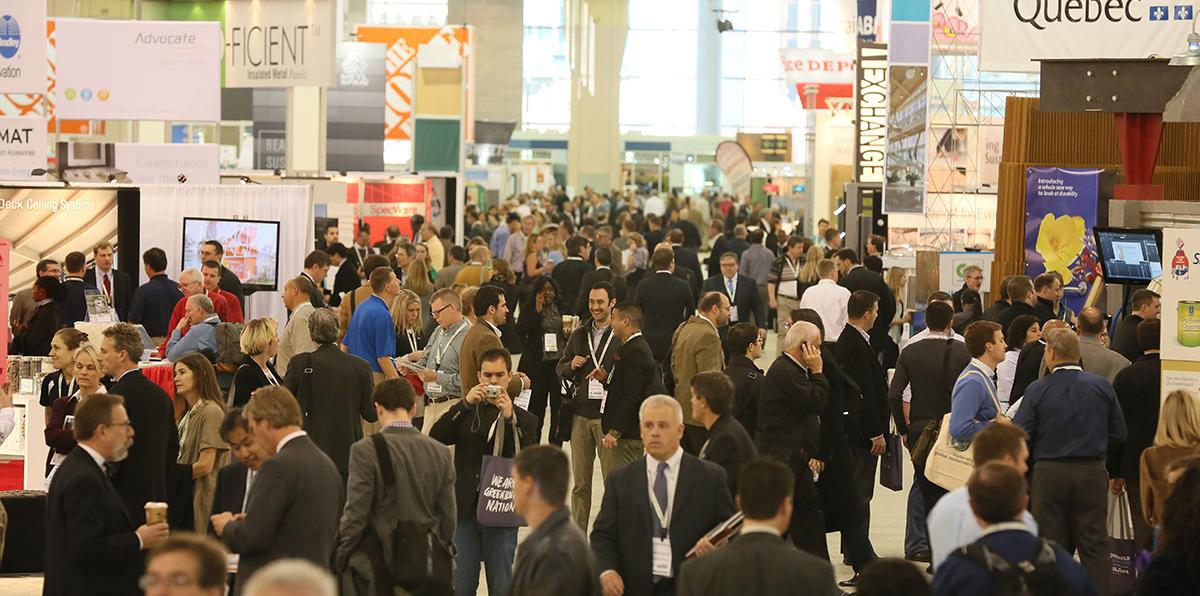

Lessons from Greenbuild

Posted by coreysquire on 11/13/14 at 1:08 pm

Recently, a few of us traveled to GreenBuild in New Orleans to see what’s new in the world of sustainability. Though the official theme of the conference was resilience (particularly relevant given the host city) a few other hot topics kept popping up. Here are three major themes that I noticed from Greenbuild 2014.

Disclosure is hip!

In 1906, journalist Upton Sinclair publish his novel “The Jungle” which revealed to the public the unsanitary and dangerous conditions in American meatpacking plants. Less than a year later, the US government passed the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act, requiring labeling and inspection to make sure no poisoned rats end up in our sausage.

Today, we are living in another jungle, one where the chemicals in our homes and businesses are damaging our health and causing all sorts of ailments, from asthma to cancer. Unlike in 1906, the government is not going to come to the rescue. This time, the architecture community, with tools like DECLARE and HPD, is shifting the market towards disclosure and working to ensure that only transparent, healthy materials end up in our buildings.

Some firms are going even further and disclosing the actual energy performance of their buildings as well as lessons learned from poor performing projects. At one Greenbuild session, an attendee from the audience asked how firms can speak publicly about mistakes without risking legal repercussion. At her firm, the in-house council wouldn’t allow any post occupancy evaluations at all because somebody might find a problem. Thankfully, this attitude seems to be coming to an end. More and more firms are talking about actual performance and sharing data that helps the entire community.

“Millennials don’t want to…”

Who are millennials and what makes them different from everyone else? How are the interests and expectations of this group going to change the industry and the world? This was a big topic this year at Greenbuild with speakers making claims that, “millennials won’t accept a traditional work environment” or “millennials want to improve the world through business” and the like. The realization is that architects need to rethink the entire built environment to accommodate the ideas of this new generation.

According to studies, millennials (born between 1980 and 2000) are more creative, more independent, less interested in rules, structure, or social norms, more secular, and more socially conscience than previous generations. The group is interested in “enjoying life now,” and not “waiting for our turn” or “climbing the corporate ladder.” The desire of companies to attract millennials and their unique skillsets has caused a mini revolution is the design of office environments. Operable windows, good air quality, urban settings, adjustable work stations, break rooms, and other amenities are becoming more common in office design. This is particularly true in the tech world, but is quickly spreading to other sectors, including architecture. The previous generation might have thought that spending nine hours in a cube farm was a fair price to pay for a chance at the corner office. If millennials don’t enjoy their work environment, they’re off to a different office that can provide them with the amenities they’re looking for.

Biophilia is now mainstream

Only a few years ago, biophilia and biophilic design were one of those things that serious people didn’t talk about. It was seen as a “touchy-feely” concept with no scientific backing, along the lines of the juice cleanse or acupuncture. Since then, study after study has come out showing the benefits of (or more likely, the risks of not) incorporating biophilic elements in buildings on health, productivity, and well-being. Biophilia is now at the forefront of sustainable design and more and more research is being conducted to see how we can get the greatest benefit.

Humans, along with all animals, evolved in and alongside a specific environment. For us, this environment was the African savanna (not a white painted gyp office with 2’ by 2’ acoustical tile) and there are aspects of this environment that we biologically long for. If you’ve ever seen an animal showing signs of stress when brought into an unfamiliar environment, this is what we are feeling at a low level every day. Over time, stress manifests itself as depression, hypertension, and all sorts of physical and psychological ailments.

By designing our buildings and cities to be a little more like nature, we can go a long way towards improving the health and well-being of our society, and now with the science and industry acceptance to back it up.