THE DOGRUN

a place to share ideas

LF30: 1984 Vickers Residence

Posted by graceboudewyns on 2/6/14 at 5:02 pm

In honor of Lake Flato’s thirtieth anniversary, the Thirty Projects x Thirty Years series has been developed to explore and celebrate the firm’s history and culture of design. Published bi-weekly, the series will highlight one project per year, starting in 1984 and ending in 2014. The projects that have been selected will give you a snapshot of the firm’s evolution as well as provide a fun and insightful collection on then and now, and ultimately, who we are today.

In the midst of George Orwell's fateful year, David Lake and Ted Flato found themselves in good company with a few other GenX phenomenons: Purple Rain was released by Prince, putting Lake Minnetonka on the map, Chrysler introduced the omnipresent minivan and changed the lives of suburban soccer moms forever, Steve Jobs was busy releasing the Apple Macintosh on unsuspecting consumers and four of today's current LF employees were just being born: Gus Starkey, Cody Knop, Heather Holdridge, Ty Reece. Despite these curious distractions they also made time to establish an architecture firm . . .

1984: Vickers Residence

By: David Lake

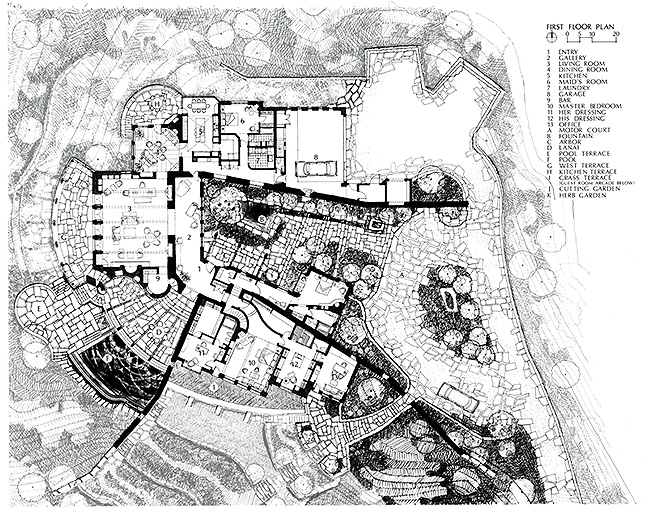

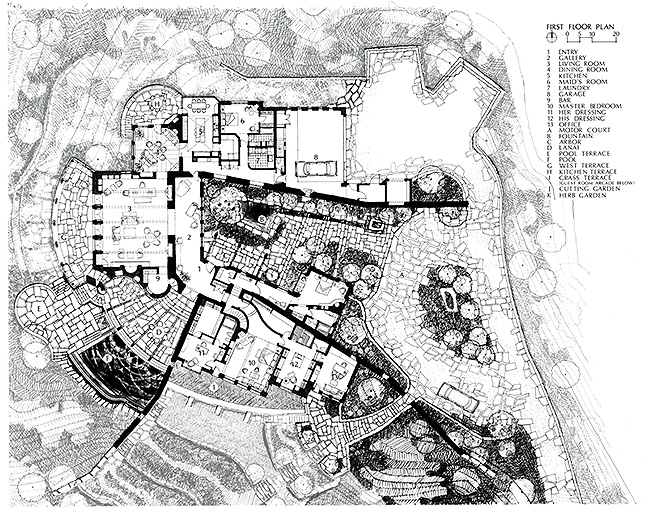

It all began with an O’Neil Ford sketch inspired by a trip to Sardinia in 1979. The quirky geometry and pinwheel plan was a departure from his orthogonal modernist roots, “Neil” claimed the romantic urge was inspired by pre-modernist sensitivities and the rough slate table he sketched upon. As usual, O’Neil snuck up to my cubicle, cigar in hand, and tossed the sketch on my table and said, “It’s a crazy mess, but I love it, make it work.

In the midst of George Orwell's fateful year, David Lake and Ted Flato found themselves in good company with a few other GenX phenomenons: Purple Rain was released by Prince, putting Lake Minnetonka on the map, Chrysler introduced the omnipresent minivan and changed the lives of suburban soccer moms forever, Steve Jobs was busy releasing the Apple Macintosh on unsuspecting consumers and four of today's current LF employees were just being born: Gus Starkey, Cody Knop, Heather Holdridge, Ty Reece. Despite these curious distractions they also made time to establish an architecture firm . . .

1984: Vickers Residence

By: David Lake

It all began with an O’Neil Ford sketch inspired by a trip to Sardinia in 1979. The quirky geometry and pinwheel plan was a departure from his orthogonal modernist roots, “Neil” claimed the romantic urge was inspired by pre-modernist sensitivities and the rough slate table he sketched upon. As usual, O’Neil snuck up to my cubicle, cigar in hand, and tossed the sketch on my table and said, “It’s a crazy mess, but I love it, make it work.

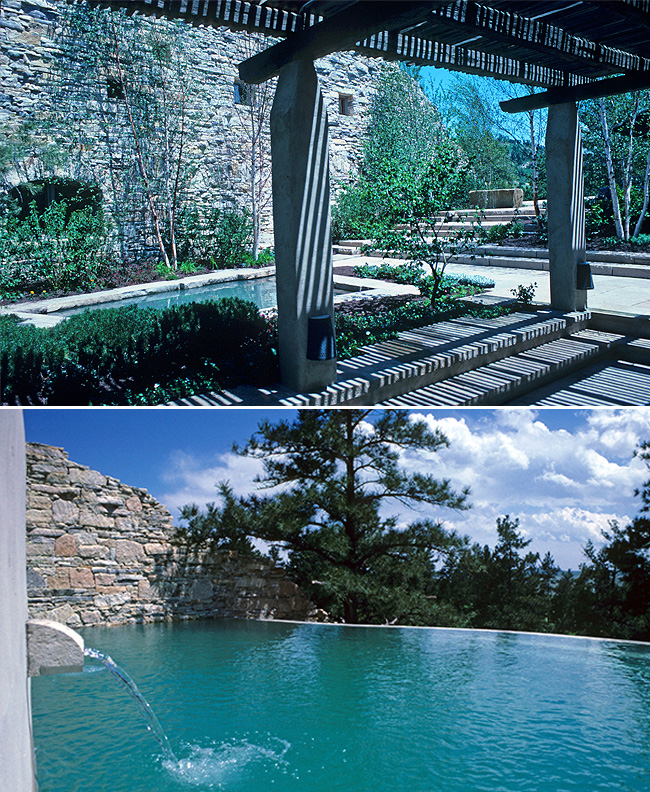

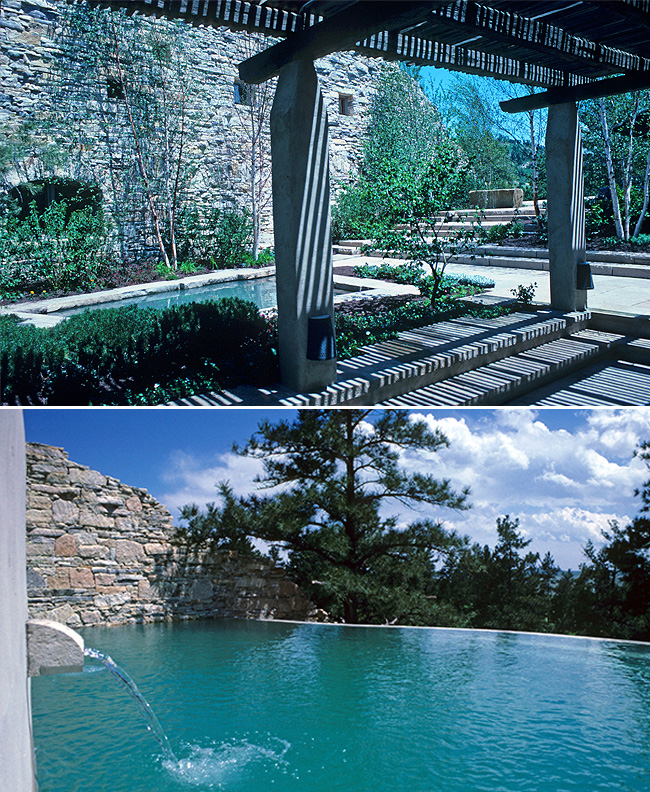

Jack and Callie Vickers were remarkable clients whose Castle Pines site was a steep ridge with panoramic views to the front range. O’Neil said, “make it like a ruin, a farmhouse built against a meandering stone wall.” The freestanding strength of the stone wall became a datum running the sites ridge line, whose stepped profile was inspired by the Anasazi . . . “you can’t beat a good ruin” O’Neil always claimed.

Jack and Callie Vickers were remarkable clients whose Castle Pines site was a steep ridge with panoramic views to the front range. O’Neil said, “make it like a ruin, a farmhouse built against a meandering stone wall.” The freestanding strength of the stone wall became a datum running the sites ridge line, whose stepped profile was inspired by the Anasazi . . . “you can’t beat a good ruin” O’Neil always claimed.

Following O’Neil’s passing in 1982, I grudgingly left Ford Powell Carson and Jack Vickers asked that I continue the construction administration. The journey of collaborating with Bubba Hunt on the masonry and other craftsman led to a succession of highly detailed elements throughout the home. But, the stonewall was the anchor, built of three different types of limestone and purposefully mimicking the Chaco walls . . . in contrast to the fluid stucco walls. The clarity of the diagram, the purpose of the stone wall as a vertebrae, has evolved in our work to become the dialogue between shelter (mass, hearth, opacity, craft) and technology (lightness, transparency, movement).

Following O’Neil’s passing in 1982, I grudgingly left Ford Powell Carson and Jack Vickers asked that I continue the construction administration. The journey of collaborating with Bubba Hunt on the masonry and other craftsman led to a succession of highly detailed elements throughout the home. But, the stonewall was the anchor, built of three different types of limestone and purposefully mimicking the Chaco walls . . . in contrast to the fluid stucco walls. The clarity of the diagram, the purpose of the stone wall as a vertebrae, has evolved in our work to become the dialogue between shelter (mass, hearth, opacity, craft) and technology (lightness, transparency, movement).

The Bartlit House 20 years later retained the eccentricity of the meandering stone walls and replaced the romantic stucco walls with a lightweight steel frame, glass hovering above strong granite walls, distilling the design to elemental walls which shelter and anchor in contrast to the delicate glass walls’ seamless connection to the outdoors.

The Bartlit House 20 years later retained the eccentricity of the meandering stone walls and replaced the romantic stucco walls with a lightweight steel frame, glass hovering above strong granite walls, distilling the design to elemental walls which shelter and anchor in contrast to the delicate glass walls’ seamless connection to the outdoors.

In the midst of George Orwell's fateful year, David Lake and Ted Flato found themselves in good company with a few other GenX phenomenons: Purple Rain was released by Prince, putting Lake Minnetonka on the map, Chrysler introduced the omnipresent minivan and changed the lives of suburban soccer moms forever, Steve Jobs was busy releasing the Apple Macintosh on unsuspecting consumers and four of today's current LF employees were just being born: Gus Starkey, Cody Knop, Heather Holdridge, Ty Reece. Despite these curious distractions they also made time to establish an architecture firm . . .

1984: Vickers Residence

By: David Lake

It all began with an O’Neil Ford sketch inspired by a trip to Sardinia in 1979. The quirky geometry and pinwheel plan was a departure from his orthogonal modernist roots, “Neil” claimed the romantic urge was inspired by pre-modernist sensitivities and the rough slate table he sketched upon. As usual, O’Neil snuck up to my cubicle, cigar in hand, and tossed the sketch on my table and said, “It’s a crazy mess, but I love it, make it work.

In the midst of George Orwell's fateful year, David Lake and Ted Flato found themselves in good company with a few other GenX phenomenons: Purple Rain was released by Prince, putting Lake Minnetonka on the map, Chrysler introduced the omnipresent minivan and changed the lives of suburban soccer moms forever, Steve Jobs was busy releasing the Apple Macintosh on unsuspecting consumers and four of today's current LF employees were just being born: Gus Starkey, Cody Knop, Heather Holdridge, Ty Reece. Despite these curious distractions they also made time to establish an architecture firm . . .

1984: Vickers Residence

By: David Lake

It all began with an O’Neil Ford sketch inspired by a trip to Sardinia in 1979. The quirky geometry and pinwheel plan was a departure from his orthogonal modernist roots, “Neil” claimed the romantic urge was inspired by pre-modernist sensitivities and the rough slate table he sketched upon. As usual, O’Neil snuck up to my cubicle, cigar in hand, and tossed the sketch on my table and said, “It’s a crazy mess, but I love it, make it work.

Jack and Callie Vickers were remarkable clients whose Castle Pines site was a steep ridge with panoramic views to the front range. O’Neil said, “make it like a ruin, a farmhouse built against a meandering stone wall.” The freestanding strength of the stone wall became a datum running the sites ridge line, whose stepped profile was inspired by the Anasazi . . . “you can’t beat a good ruin” O’Neil always claimed.

Jack and Callie Vickers were remarkable clients whose Castle Pines site was a steep ridge with panoramic views to the front range. O’Neil said, “make it like a ruin, a farmhouse built against a meandering stone wall.” The freestanding strength of the stone wall became a datum running the sites ridge line, whose stepped profile was inspired by the Anasazi . . . “you can’t beat a good ruin” O’Neil always claimed.

Following O’Neil’s passing in 1982, I grudgingly left Ford Powell Carson and Jack Vickers asked that I continue the construction administration. The journey of collaborating with Bubba Hunt on the masonry and other craftsman led to a succession of highly detailed elements throughout the home. But, the stonewall was the anchor, built of three different types of limestone and purposefully mimicking the Chaco walls . . . in contrast to the fluid stucco walls. The clarity of the diagram, the purpose of the stone wall as a vertebrae, has evolved in our work to become the dialogue between shelter (mass, hearth, opacity, craft) and technology (lightness, transparency, movement).

Following O’Neil’s passing in 1982, I grudgingly left Ford Powell Carson and Jack Vickers asked that I continue the construction administration. The journey of collaborating with Bubba Hunt on the masonry and other craftsman led to a succession of highly detailed elements throughout the home. But, the stonewall was the anchor, built of three different types of limestone and purposefully mimicking the Chaco walls . . . in contrast to the fluid stucco walls. The clarity of the diagram, the purpose of the stone wall as a vertebrae, has evolved in our work to become the dialogue between shelter (mass, hearth, opacity, craft) and technology (lightness, transparency, movement).

The Bartlit House 20 years later retained the eccentricity of the meandering stone walls and replaced the romantic stucco walls with a lightweight steel frame, glass hovering above strong granite walls, distilling the design to elemental walls which shelter and anchor in contrast to the delicate glass walls’ seamless connection to the outdoors.

The Bartlit House 20 years later retained the eccentricity of the meandering stone walls and replaced the romantic stucco walls with a lightweight steel frame, glass hovering above strong granite walls, distilling the design to elemental walls which shelter and anchor in contrast to the delicate glass walls’ seamless connection to the outdoors.